Heart Work / Rewriting a Literacy Crisis / Episode 3

Rewriting a Literacy Crisis

Episode 3: It Takes Time and It Definitely Takes Heart

Back in Pendergast, the ultimate question: Did it work? In this final episode, Lauren returns to the district to find out and speaks with renowned education writer Natalie Wexler on the missing piece in reading instruction. Could the answer have been in front of us all along? Listen and find out.

From Imagine Learning, I’m Lauren Keeling, and you’re listening to Heart Work, an honest profile of America’s educators.

When you care so deeply, you make hard choices, and you do hard things, and you fail forward, and you try again, because that’s what great teachers do. They push forward even when it seems impossible, and they come out on the other end saying, “Whew, that was a wreck, but man, did this go really well! I can’t wait to try both of those things again and see how I can make it even better.”

Every teacher I talked to, every administrator I talked to, every human in those two districts that I spoke with — they weren’t interested in being right; they were really interested in doing right.

It’s been three years since the Pendergast Elementary School District overhauled how they teach reading. In episode one, we saw the shift up close.

A painted playground map shows Arizona and its neighboring states.

The question now is simple: Did it work? Today, I’ll find out, and I’ll also talk with one of the leading voices in the movement to rethink how we teach reading comprehension.

Natalie Wexler: Let me see if I can start my video now. Yeah, there I am. OK.

My name is Natalie Wexler. I am an education writer. I’ve written a book called The Knowledge Gap — The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System and How to Fix It, and I have a new book coming out in January called Beyond the Science of Reading: Connecting Literacy Instruction to the Science of Learning.

I started writing about education because it seemed incredibly important to me — particularly how we can raise education outcomes for all kids, but also narrow the gap between kids at the upper and lower ends of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Lauren: How did you come to identify the knowledge gap as something that was critical to education?

Natalie: It seemed to me there was a missing piece that could make teachers’ jobs easier and students’ jobs of learning easier as well. The term science of reading has often come to be defined as just more phonics, and it’s way more complicated than that.

There is a lot of scientific evidence related to reading and reading comprehension that should be included in the term science of reading, but it often gets left out. And there are ways in which the standard approach to teaching reading comprehension also conflicts fairly dramatically with what science tells us about how that process works.

Having knowledge of the topic you’re reading about is really helpful to comprehension, and beyond that, the more general knowledge and vocabulary you have, and particularly more academic kinds of knowledge and vocabulary, the easier it is for you to understand just about anything you try to read. So you become a better general reader with more of that general knowledge.

Natalie’s point echoes what I first learned from her book, The Knowledge Gap, that a lot of students are unfairly disadvantaged because they don’t have adequate background knowledge about certain topics or subjects. And that missing knowledge creates a gap between being able to read the words on a page and actually understanding what those words mean.

That message also resonated with Pendergast’s principal, Mr. Gonzalez. Natalie Wexler’s work helped shift the way he thought about reading — and about how it should be taught.

Mr. Gonzalez: I go back to the research from Natalie Wexler. In her book, she talks about baseball, right? And if we don’t have that background, then how are we going to read a book about baseball?

It’s meaningless to us, right? But if you played baseball and you read other books about baseball, then you’re going to comprehend what you’re reading. The ability to dive deep within that text is so important for comprehension, especially with our students who are English language learners. Really developing those opportunities for students to go back and cite text evidence has really helped us in closing that achievement gap.

Ms. Barrett: We did Basel. We taught Basel. Monday, we did this. Tuesday, we did this. Wednesday, we did this.

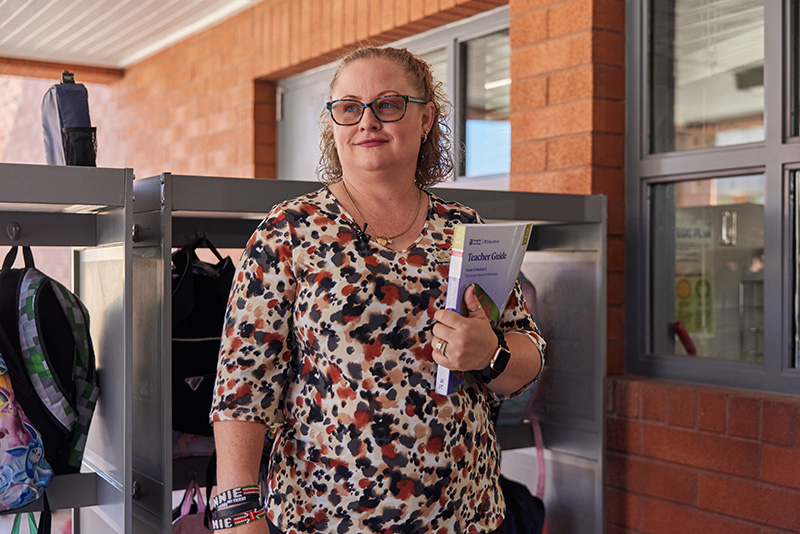

Ms. Barrett stands outside her classroom, ready to welcome her students as the day begins.

That’s Ms. Barrett — she teaches second grade and is who we’d call in administration, an early adopter.

Ms. Barrett: Whereas now, it’s not on a five-day schedule. It’s inclusive. It flows from topic to topic. It’s seamless. The kids enjoy it, and it just makes learning a lot more fun.

(Students singing)

Ms. Barrett (to students): Good job, guys. So I want you to go back and look at the poem, OK, and then we’re going to share those out, and then we’re going to talk about it.

Ms. Barrett: When we’re doing our teaching, the first unit is building that background knowledge, but then the modules build on each other, and so a lot of times my kids are taking ownership and they’re taking leadership, and I can step away and I can let them teach.

Lauren: So you get to facilitate?

Ms. Barrett: Right.

Lauren: How does that feel?

Ms. Barrett: It feels really good. Yeah, it feels really good.

There’s this old phrase, “the sage on the stage”. It refers to a teaching style where the teacher delivers information, often through a lecture or presentation, and students are expected to sit, listen, and absorb.

I’m sure we’ve all experienced that at some point in our lives. But in this classroom, there’s no stage. Students are moving around, leaning into the work, excited to be learning. Ms. Barrett is crouched beside a table, asking a question, and really listening to the answer. She’s inviting students to participate in the process of learning, not just leading it.

Natalie: Kids, when they are still learning to decode, the main way they’re going to be acquiring knowledge is not through their own individual reading. It’s going to be through oral language and listening to books being read aloud and talking about the content of those books, using the vocabulary that they’ve just heard in those books, that’s going to transfer that information to long term memory.

Ms. Barrett (to students): Why do they get a scarf for Pat? Hmm, why do they get a scarf for Pat? Because it’s cold and he needs to what?

Student 1: Be warm.

Ms. Barrett: They want to be warm. So what does James — how does it relate back to our reading? To being an independent reader?

Student: I can read in my head.

Ms. Barrett: Oh, you can read in your head? Nice. That’s awesome. Richard?

Student 2: I can read quietly.

Ms. Barrett: You can read quietly.

Student 3: I can read very big words.

Ms. Barrett: You can read very big words.

Natalie: Eventually, when their foundational reading skills catch up to where their background knowledge is, the background knowledge will kick in to enable them to read independently about a range of topics.

Lauren: Do you feel like the children are growing in that space?

Ms. Barrett: Absolutely. They’re growing with their confidence. They’re growing with their communication from peer to peer and from peer to teacher. The kids just love to dive in, and they have become very independent and excited to learn.

I see that independence in the way they talk about their work.

Lauren: So I don’t know what the centers are. Can you explain the centers to me?

Student 1: First, we put up the timer for 15 or 20 minutes, and then we start our centers.

Student 2: There’s a writing one, there’s a reading, there’s goldfish, there’s Ms. Barrett. We have computers. Wherever our names are, we do that center.

Student 3: Like, if we have writing, we just bring our book with us and we write in it.

Student 1: We write about butterflies sometimes and the weekend.

Student 2: When the timer goes off, we switch centers and it keeps going until it’s lunch.

A young student in Ms. Gabhart’s class works on the smartboard during a classroom activity.

Natalie: Kids get it, and I mean, I’ve been in classrooms where they don’t want the teacher to stop reading. They still have things to say when it’s time for the discussion to end. There’s this excitement in the air. And that is just as much about teaching reading as teaching phonemic awareness and phonics and all of those things that also need to be taught.

Ms. Irvin: In module four in fourth grade, the students have to identify a service project that they’re going to work together on. We spend some time talking about how kids make a difference in their community. They come up with a list of issues they feel that they can impact in their community, and then they start working on a project for that.

Ms. Irvin tells me about the PSAs her students are creating.

Ms. Irvin: One year, my kids worked on collecting items for the Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and this year, they have identified our lost and found as a huge problem on our campus. It was overflowing with bags of clothes. And so they are working to get that all organized, get it out to the students so they can start reclaiming their items. We have a whole list of videos and informational text that teaches them about other students and kids who have made a difference in their community, and their end result is that they create a PSA about the results that they had.

(Student conversation)

Lauren: Did they get excited about this? Do they love this?

Ms. Irvin: Oh, they’re very excited about it. They love asking everyday, “Can I go work on the lost and found? I finished my work. Can I go work on lost and found?” And so they’re really involved in it.

Ms. Johnson: So with the PSA, do we need to understand our audience? Okay, so let’s put that on our list as well.

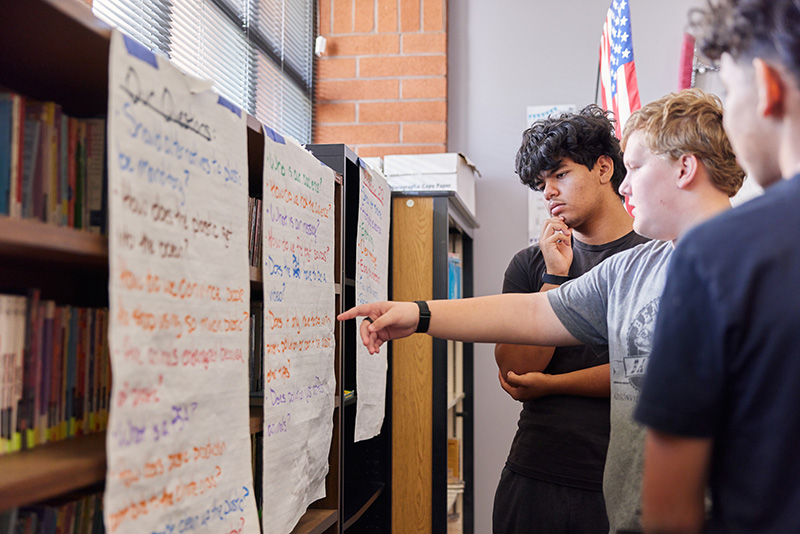

In Ms. Johnson’s seventh-grade class, the PSA’s addressed a global issue: plastic pollution.

The contrast struck me. The fourth graders took on a problem they saw every day. By seventh grade, they had the knowledge and the words to reach further, to connect something global back to their own community.

Student 1: So, should we try to expand this to more than just Avondale, Glendale?

Student 2: Well, if we focus on Avondale, then we could do something that relates to people who live in Arizona?

Student 1: And then — and then build up to make it bigger?

Student 2: And we can bring more awareness to it, yeah.

Student 1: Yeah, good idea.

Student 2: So we’ll focus on recycling, instead of the alternatives?

A group of students collaborate in front of handwritten posters, discussing their ideas during a classroom activity.

Ms. Johnson: I’m starting to see my students bring in ideas and things that they’ve learned in other classes to solidify their statements, and that is a neat thing. Many of them have picked up decoding skills, and their vocabulary has expanded. They’re able to read with better flow. So all of the pieces seem to come together at the end of the school year.

It’s been kind of funny because one of my students wanted an extra recess or something. He made a ten-slide PowerPoint with his argument, stating what he wanted, why he wanted it, and why he felt he could get it. So we did a little negotiating, and it worked. So it was fun. He got an extra recess. And so it was really fun. And that’s the beauty of it, when they start applying those skills that I have taught them.

In Pendergast, the changes seem to be working. And in Philadelphia, I saw what’s possible when educators commit to doing things differently.

Lauren: But, if you were to point to some specific data or some evidence. You know, when your district comes to you and says, “Prove to me that this is working,” how would you do that?

Ms. Irvin: Consistently, I’ve had some of the highest scores in the state reading assessment. My grade level last year, within our own school, had the highest percentage of students passing in all of the grade levels that took it.

Mary: 67% of our kindergarten students showed what was called aggressive growth in their reading at the winter benchmark.

Carina: And we’re anticipating it being higher here at our spring benchmark.

Ms. Johnson: So when we take district pretest, district posttest from the previous year in state testing to the current year and state testing, I see growth every year in my students.

Natalie: Teachers see what’s happening in their classrooms. They know things are changing, but it is harder to get that quantitative data based on what we know about what cognitive science tells us about how important knowledge is to comprehension. We have lots of evidence of that. We don’t need to wait for more experimental evidence in order to make this kind of switch.

In Philadelphia and Pendergast, I saw how the debate over reading plays out in real classrooms.

And at the heart of it all isn’t programs or policies. It’s the teachers who show up every day. And it’s the students doing the hard work of learning. That’s what I’ll carry with me. That no matter the district, the program, or policy, change happens because of them.

Natalie: We’ve been giving kids these excerpts, brief texts, and using them as a means to this end of developing reading comprehension skills and turning reading into this kind of task that you have to do. But there’s another way to approach reading, which is like, this is really fun.

Reading is about so much more than scores or assessments. Through books, I’ve lived a thousand different lives. I’ve traveled to far-off places and spent time with people who exist only on the page.

I don’t think we really learn without stories — without history, without firsthand accounts, without the folklore and the fiction that carry voices across time.

Natalie: There is evidence showing that fiction helps develop empathy, and I think that is what helps develop empathy is that transportation into this other world, into other people’s shoes.

Empathy, perspective, possibility — that’s what reading gives us. That’s why this work matters.

Kelsie: I love seeing my students across my campuses get to be their authentic selves while they’re learning and growing in their classrooms with teachers that are excited to show them what they are able to do and how far they can stretch themselves to meet the expectations, and then go past those expectations and carry lifelong skills into the future.

I hope that whoever listens to this podcast, whatever space you’re in as an educator or administrator or parents or students, I hope that what you walk away knowing is that you’re not alone.

And for the people who are new to change, struggling through the middle of change, or planning for change. You’re just not alone.

For the administrator who’s crying in her office because the change is really hard, and some people that you love are really struggling with it, you’re not alone either. You’ll get there on the other side. And you’ll be glad for it.

Ms. Johnson: That’s when you know students are really learning.

Change takes time, and it definitely takes heart. And while the debates keep going, teachers will be in the classroom, doing the real work.

00:00 Introduction

01:11 A conversation with Natalie Wexler

04:05 The power of making a shift

08:52 Fourth-grade projects with purpose

10:48 Seventh-grade voices for change

12:37 Measuring what really matters

15:53 You are not alone

About the Host

Lauren Keeling is a seasoned education professional with a unique blend of experiences. A former broadcast journalist, elementary teacher, and principal, she now combines her passion for education with her love of storytelling at Imagine Learning. Above all, Lauren is a dedicated literacy advocate pursuing a doctorate in Leadership with a focus on Public and Non-Profit Organizations to further her impact on education nationwide.

Join the Club

Heart Work is our platform for telling educators’ stories. Sign up for the Heart Work Club to be among the first to share yours. You’ll also get the latest podcast episodes, articles, and exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox.