Heart Work / Rewriting a Literacy Crisis / The Case for Knowledge Building in Reading Instruction

The Case for Knowledge Building in Reading Instruction

Lauren Keeling | 10/21/2025 | 6 minutes

For every young reader, there’s a quiet moment when learning to read stops being about sounding out words. But what follows? Former teacher and principal Lauren Keeling explores the shift and reflects on how we move from the “reading wars” toward a model of literacy that honors both the science of reading and the humanity of why we learn to read — and truly gives students the skills they need for the real world.

There’s a moment in every elementary teacher’s school year when the question shifts from “Can they sound it out?” to “Do they understand what they are reading?” It’s a quiet shift, but it marks the beginning of deeper work for themselves and their students. The work that asks not just how students learn to read, but why they read, what they know, and how that knowledge shapes their understanding of not only what’s on the page, but what’s in the world.

We know that reading is more than letters and sounds working together on a page. Reading is where skill meets substance, where meaning is made, and where connections begin. But for many of us, we learned the hard way that while decoding is essential, it’s not enough.

We’ve Missed the Mark

The latest NAEP scores tell a sobering story: we are not where we need to be. In 2024, reading scores for both fourth and eighth-grade students declined again, continuing a downward trend that began well before the pandemic.

Only 31% of fourth graders score at or above the NAEP Proficient level. Even more troubling, 40% of fourth graders and a third of eighth graders scored below the Basic level. That means that they struggle with even the most fundamental reading tasks.

But these numbers aren’t just statistics. They represent children — children who are being asked to read texts they cannot understand, answer questions they cannot access, and engage with content they’ve never been given the tools to explore. Many might be able to make words from the letters they see and sounds they hear, but as the scores suggest, most can’t cross the bridge to making meaning from those parts and pieces.

We’ve spent years debating how to teach reading, but somewhere along the way, we lost sight of why it’s so important.

The Case for Knowledge Building

Most of you will be familiar with what is now commonly dubbed the “reading wars.” It’s a debate that has long divided educators into camps: phonics versus whole language, skills versus meaning, decoding versus comprehension. Somehow, the rich, layered process of learning to read has been reduced to a simplistic tug-of-war. Yes, students must learn to decode. Phonics instruction is foundational, especially in the early years. But decoding alone does not create readers. It creates word-callers — students who can pronounce the words but cannot grasp their meaning.

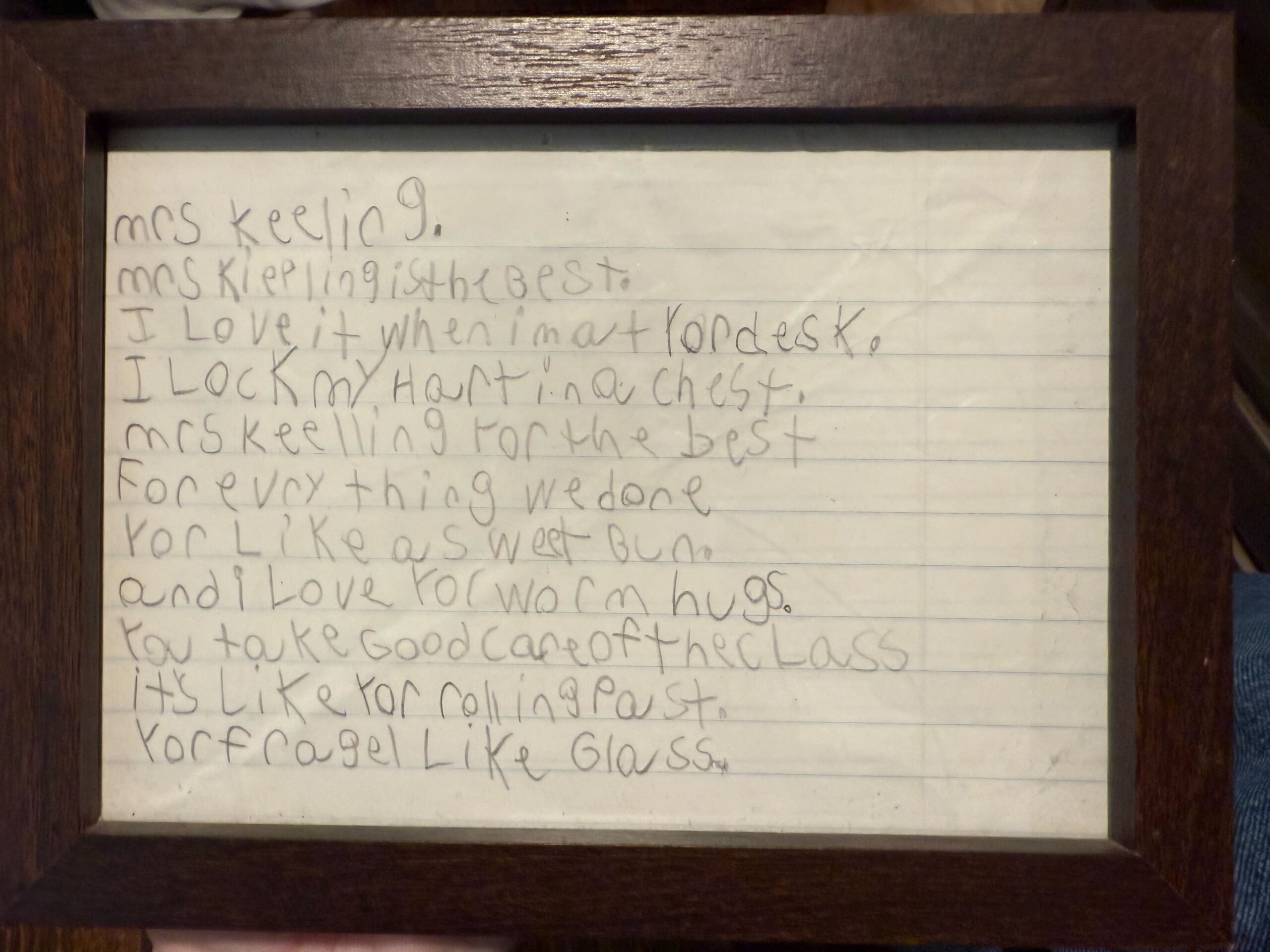

I began my career as a whole language teacher, raised by the very practices I was now passing on. My classroom was filled with stories, rich conversations, and joyful reading experiences. But somewhere along the way, the ground began to shift. Suddenly, phonics was at the forefront of reading instruction, and I found myself learning the foundations of letters and sounds alongside my kindergarteners. It was a humbling experience, transformative in fact, and it changed everything about how I taught reading.

But even as my students grew more confident in sounding out words, a new challenge emerged. They could read the words, but they couldn’t always reach the meaning. They could decode, but they couldn’t connect. That moment, that tension between skill and understanding, was the beginning of my journey into knowledge building. It was the realization that reading is not just about getting through the words. It’s about getting into them.

When we focus solely on decoding, we strengthen one part of what we call Scarborough’s Reading Rope. But without the other strands, especially background knowledge, students can read the words but can’t grasp the meaning. As Natalie Wexler writes in The Knowledge Gap, “You can’t comprehend a text if you don’t have enough relevant knowledge about the topic to make sense of it.”

The Power of Knowledge Building

I’d like you to picture a group of kindergarten students sitting on their classroom carpet listening to a story about the beach. The words are vivid: waves crashing, sand between toes, seagulls squawking overhead. For many children, the story feels distant no matter how intently they listen. Why? Because the beach is not a lived experience. They’ve never seen it, felt it, or heard it, and the vocabulary feels foreign. Comprehension falters — not because they lack ability, but because they lack context. They can’t practice reading, speaking, and listening skills because they’re overwhelmed by trying to catch up with the content they just don’t understand.

Conversely, when content is thoughtfully selected and rooted in what children know, the words are no longer abstract. For early readers, this is critical. And it can’t be left to chance. Not all students have equal access to dinner-table conversations, museum visits, or vocabulary-rich environments, which makes it even more important to build knowledge intentionally. When we do, we reduce students’ cognitive overload, give them the schema they need to make sense of complex texts, and scaffold their learning with real-world connections.

Now, I want you to picture a kindergarten classroom exploring the topic of toys and play — something much more familiar to five- and six-year-olds. Students are interviewing one another, asking questions like, “What’s your favorite toy?” and “What game do you love to play?” One child draws a picture of their favorite stuffed animal, another writes a few words about tag, and a third shares a story about using building blocks at home. When the teacher gathers the class to share, every child has something to say. They speak with joy, confidence, and connection because the topic is familiar. Most importantly, they’re able to focus on the skills of reading and writing because the meaning is already within reach.

It’s Both/And … and More

Building background knowledge isn’t just about giving early readers information. It gives them access. Last year, I visited the School District of Philadelphia — you’ll hear why in our second podcast episode — and met with Deputy Superintendent, Dr. Dawson. He said to me, “The question we need to ask ourselves is, ‘Do they have the skills to be able to succeed in life to set them up for a limitless future?’” For too many students, the answer is no — and through no fault of their teachers.

Moving beyond the “reading wars,” decoding versus knowledge, and all the other practices we argue about means letting go of sides and moving toward something better: a literacy model that honors the science of how children learn to read and the humanity of why they need to. A model that teaches students to decode words … and decode the world.

About the Author

Lauren Keeling is a seasoned education professional with a unique blend of experiences. A former broadcast journalist, elementary teacher, and principal, she now combines her passion for education with her love of storytelling at Imagine Learning. Above all, Lauren is a dedicated literacy advocate pursuing a doctorate in Leadership with a focus on Public and Non-Profit Organizations to further her impact on education nationwide.

Join the Club

Heart Work is our platform for telling educators’ stories. Sign up for the Heart Work Club to be among the first to share yours. You’ll also get the latest podcast episodes, articles, and exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox.