Heart Work / Rewriting a Literacy Crisis / Episode 1

Rewriting a Literacy Crisis

Episode 1: Some Birds Can’t Fly but They Can Swim

Across the country, a movement for change is taking hold in a desperate attempt to improve reading scores. In this first episode, host Lauren Keeling reflects on her own experience with the reading crisis and visits Pendergast Elementary District, where a bold overhaul of reading is underway. Listen now to hear what happens when a district bets big on change.

From Imagine Learning, this is Heart Work, an honest profile of America’s educators.

The moment in my career that simultaneously broke me and knit me back together was when I listened to the podcast, “Sold a Story.” I know it was life-changing for educators across the nation, across the world. It swept us up in a way that we weren’t expecting and didn’t anticipate. And so many educators were like me in that moment going through that experience of like, what in the world is phonics? How do I help children understand phonological awareness when I don’t know it. I wasn’t taught it. That’s not what my curriculum is asking me to do. I’m doing all these practices and actually, I really love guided reading. It’s a special moment in my classroom and I get hands-on opportunity and time and stories with my children and now you’re telling me not to do it that way? I’m crushed. So I remember listening to that podcast and having this moment where I just lost it. I cried and cried and cried because my heart told me that I had been teaching children wrong for so long. And I absorbed that in a way that made me feel like I had kept children from being able to read.

The story you just heard is my own. And it’s one shared by educators nationwide — the moment we realized we could do better. But first, who am I? I’m Lauren Keeling and I have what I like to call a mosaic background. I’ve been a broadcast journalist, a kindergarten teacher, and an elementary school principal. Now, I’m part of Imagine Learning, where I’ve been fortunate enough to knit all those experiences together, as a communicator with the heart of a teacher and the earned wisdom of a principal.

In January of 2025, the latest results from the Nation’s Report Card came out, and it wasn’t good news. Reading scores have dropped again. This time to historic lows, with the lowest performing fourth and eighth-grade students posting the worst scores in 32 years.

NBC News: Only about 33% of fourth graders can read proficiently.

ABC News: The older a child gets, the harder it is to read proficiently.

ABC News: There’s a lot of work that we have to do here.

In the United States, the way we teach reading has a long and pretty rocky history. With the debate on what works best going back and forth for decades. Whole language on one side, science of reading on the other. For years, whole language approaches dominated classrooms. But now, as scores continue to plummet, districts are making a change. Turning more and more to the science of reading in an effort to improve them.

Ms. Johnson: We know that students are behind. We know that they’re struggling to get caught up.

Principal: If our students are not able to comprehend what they’re reading, we are not doing our due diligence as educators.

Ms. Johnson: I see growth every year in my students. Is it where I want it to be? No. But are we making progress?

Garden Lakes Elementary School in the Pendergast Elementary School District.

It’s a warm, sunny morning in Phoenix, Arizona. I’m in the Pendergast Elementary School District, where, three years ago, they completely overhauled how they teach reading. I want to know what changed — and if it’s working. Today, I’m visiting a few schools. We pull up to the first one and the energy is good. You can hear it: the familiar sounds of another school day beginning.

(Atmos: A car door closes. Students shout in the school yard. A teacher welcomes them at the door. A person laughs.)

I’m introduced to Mr. Gonzalez, the school principal.

Mr. Gonzalez: Good afternoon!

He reaches out and shakes my hand and immediately starts telling me about his students and what a privilege it is to give them a love of reading — a love impressed upon him by his parents.

Mr. Gonzalez: I came from an immigrant family. My parents immigrated from Mexico to the United States, and they always taught us about education and about the love of reading. So that’s what I want to instill in the students here. If our students don’t know how to read, if our students are not able to comprehend what they’re reading, we are not doing our due diligence as educators.

It turns out Mr. Gonzalez and I have a lot in common, both of us working as elementary principals during the Covid-19 pandemic. We reflect on those uncertain days — on the fear of it all — and as we talk, I find myself transported back to 2020. I remember feeling so worried about my kindergarteners missing out on the second half of the school year — that critical moment when they begin transitioning into early readers, and also about my first graders losing the foundational skills to bridge them from learning to read to reading to learn.

I shake off the memory as Mr. Gonzalez and Kelsey, the director of Interdisciplinary Literacy, offer to take us for a tour around the school. Partway through, we’re met by this larger-than-life personality. Kelsey says, “Hey Mr. A. It’s good to see you.” Mr. A. smiles at us, quick to respond, “Oh, you finally brought cameras to put me on national television.” Everybody laughs.

Typically, a school guidance counsellor wouldn’t be my first choice to interview for a series on reading, but Mr. A’s voice is unique. I can tell. We learn that he uses stories to help students build life skills — resilience, hope, empathy.

Mr. A: Kids have to feel a sense of belonging, right? They have to feel a sense of ownership and that they’re a part of something. And so when they see that Timmy in the story looks or acts or comes from a neighborhood just like theirs, it’s amazing for them. They feel included. They feel like they are part of the story. They feel like they can really relate to the characters, which influences their love of reading, influences their love of storytelling and their desire to learn more.

Later, I talk to eighth-grade student Aylynn about this. She’s hiding behind beautifully styled hair. And tells me that she’s been having a hard time lately.

Aylynn: I mean eighth grade’s not what they say about it. It’s not all fun and games. It’s hard, you know? I don’t know, that’s probably me, but it’s pretty hard.

But she loves reading stories and writing her own — going into and creating worlds. She wants to be an author one day.

Aylynn: You go into your own world for a moment. Like, if someone’s talking to me and I’m reading the books, I wouldn’t hear them usually.

She shares with me that stories have helped her empathize with others and why that matters.

Aylynn: I believe that everyone should learn how to empathize because, like, it makes people a better character.

Mr. A: Reading is your passport to anything. That’s why we really emphasize it obviously at Via De Paz, but really in schools across the country.

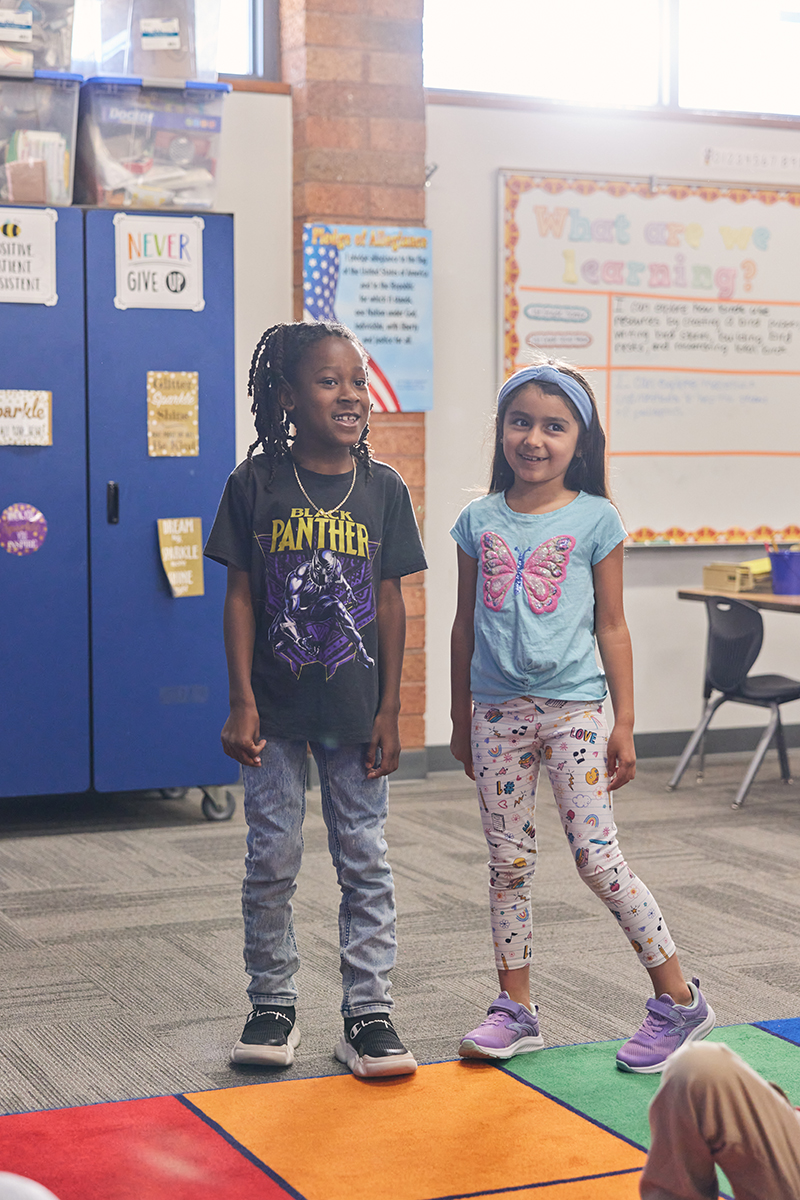

Mrs. Gabhart’s first-grade students learn about different types of birds.

Two students sing a song about birds.

(Atmos: A group of young students sing with their teacher.)

Students singing: Birds are helpful, birds are helpful, did you know, did you know? Birds can carry seeds, birds can carry seeds.

Mrs. Gabhart: When my children were in first grade and learning how to read, they read very simplified books.

My first classroom visit of the day is first grade. Mrs. Gabhart — who you just heard — has been teaching for a lifetime. She has had an impact on hundreds of students and is in her last year of being an educator.

Mrs. Gabhart: What we’re reading is much more sophisticated language, it’s much more complex topics, and it digs a lot deeper. And that’s the thing I really like because that sparks their interest a lot.

(Atmos: Classroom sounds. Students chatter.)

Mrs. Gabhart (in classroom): Especially, especially this book. This book is great because it tells us how birds. We’ve talked about, people say, why care about birds?

Mrs. Gabhart tells me how much her students love learning about birds and shares a conversation she had with the mother of one of her students recently. She told Mrs. Gabhart, “I go home every day and I ask my daughter, ‘What did you learn today?’ and she can’t wait to tell me everything she learned about birds. It’s amazing to see her so excited about learning.”

Mrs. Gabhart (to students): Does it have two detailed sentences that include evidence? Prove it to me, right? And tell me how or why you can say that. And a conclusion. Did you say again in a different way that birds are helpful? That’s why birds are helpful. Then we’re going to look, did you spell the word bird correctly? And other words that are sight words. Did you spell those correctly? Those are the things you’re going to look for today. Okay, are you ready?

(Atmos: A student writes on paper with a pencil — light scratching sound.)

Student 1: Did you spell birds correctly? Did you spell B? Tell me the letters you spelled.

Students 2: B I R D S

Student 1: Birds, some birds, some bird, some bird doesn’t make sense. We have to like fix if we don’t have a period or capital letter.

Student 2: I don’t have a period.

Student 1: Then we should have a period.

Student 2: Well because I wasn’t finished with my sentence.

Student 1: Okay, they give us food so we can eat, this is why birds are helpful.

Just on the other side of the wall is Ms. Rolph. She’s brand new to teaching and discovering her place in this world.

Ms. Rolph: So in Mrs. Gabhart’s class, they get the basic background knowledge that they need about birds and then they come into my class and they get to show what they’ve learned and do hands-on activities and just explore. So explore what they learn, create things, um, be birds building nests so they get to jump right in and do all the things they learned about.

First-grade students build birds’ nests out of colorful chenille stems.

Student 1: Wait, look you can use these! You can pull these off from this.

Ms. Rolph (to student): So you added a lot of stuff, what did you add to your nest?

Student: Oh I added like, I saw that instead using these, I could use this, like a… I can use that big knot.

Ms. Rolph (to student): So birds just take anything they can find, huh?

Student: Yeah, like branches.

Ms. Rolph (to student): Like branches, remember that book we read they were taking horse hair, they were taking all kinds of stuff.

Kids: String!

Ms. Rolph (to students): They were taking strings from someone’s shirt, they were taking everything they can find.

Boy: Someone’s hair!

Ms. Rolph (to students): Yeah!

Girl: I like it. I love my nest.

I watch Ms. Rolph interacting with her students. She never tells them exactly what to do. Instead she asks them, “What do you think? What do you know? And what do you wonder?” She’s teaching them to be problem solvers, all the while supporting and enriching the learning that began next door in Mrs. Gabhart’s class.

Ms. Rolph discusses materials students could use to build their bird’s nests.

Lauren Keeling (to students): Tell me about labs.

Student 1: They’re really fun.

Student 2: We were writing the story and making a bird nest. They have different types of beaks. Some of them have upside down ones, like the flamingo.

The level of knowledge they have about all kinds of birds is incredible, especially for seven-year-olds.

Girl: Some birds can’t fly, like penguins don’t fly, but they can swim.

I sit down with Mary and Carina, two instructional coaches.

Carina: We were all about reading first, explicit phonics instruction, and really following the research that the National Reading Panel had put out. We were getting some gains with that and we put away, like I tell people, 20 years ago we put away Play-Doh, we put away all these pieces where the children had hands on, building that stamina and the muscles, right? And now it’s nice to see, all these years later, that yes, there’s pieces for explicit phonics instruction and this continuum of how children learn to read, but also there’s opportunities in labs, right, for verbal reasoning and vocabulary development and background building. And the children have those hands-on opportunities to apply what they are learning in the module to their labs time.

Mary: When I started, it was very whole language. We were all about the whole child and the whole language. We would give them a book and say, “If you practice it enough, we’ll get it.” And then the phonics came in and we knew that that was so critical to reading, but we lost so many things. And I think Imagine Learning brings it all together. I think we have the phonics components. We have direct teaching of what needs to be directly taught. There’s exploration for kids. And they have some choice in what they’re going to research or a little bit of choice in what they’re going to learn about, and so I think that gets a lot of buy-in.

Carina: And we’re bringing real literature back.

This stands out to me. It’s a common misconception that the science of reading is all phonics. I can only speak from my own experience, but I think phonics gets so much attention because it’s the part we understood the least. I wasn’t taught phonics and I had to spend a full year learning it. Phonics are important, yes, but there are so many other parts and pieces that help a child become a proficient reader. It’s more than phonics. More than phonological awareness. More than morphology. More than sentence structure and syntax. More than real literature. More than comprehension. What it is, is the sum of all those things and more.

Mary and Carina understand this. So does Mr. Gonzalez. He walks me through the district’s path to an evidence-based literacy program.

Mr. Gonzalez: Before, our curriculum was more basal-based, right? Where there were short stories and it wasn’t even a whole story, it was part of that story. And then one week they read the short story and then off next week they’re off to a next story and then off to a next story.

Natalie Wexler — some of her research helped us really understand that looking at schools that were closing that achievement gap. And one of the biggest things is the ability to read a book from cover to cover.

Natalie Wexler’s book The Knowledge Gap — it’s linked in the reading list in this episode description — was what first made me see the problem differently. Her argument is simple. If students don’t have background knowledge, they’re already at a disadvantage. Because without it, the playing field isn’t fair. If they don’t have the general world knowledge or regular exposure to complex language, they may not have the necessary foundational understanding to fully engage with what they’re reading. If a student is reading a passage about ocean life but they’ve never seen the ocean or been to an aquarium, yes, they may be able to decode every word just fine, but they’re missing the context that brings meaning to the text. And that makes comprehension much harder than it should be.

Ms. Irvin reads “The Hope Chest” with a student.

(Atmos: Classroom noise — students singing softly in the background.)

I’m back in the classroom. Now, with Ms. Irvin and her fourth-grade students. They’re reading The Hope Chest by Karen Schwabach, a book about a young girl, Violet, who runs away from home to look for her sister. The search takes her to Tennessee, where she discovers not just her sister, but a new friend and a cause: women’s suffrage. I’m walking around this classroom, this fourth-grade classroom, and these children are young and their experience in the world is not vast. But this book has some really challenging topics — even for adults — so I ask Ms. Irvin, “Why this book? Why such a challenging book for children of a young age?”

Ms. Irvin: Well, right now, we’re learning about how you can make a difference in the world, and we’re coming off of learning about the Civil War, and those kinds of rights, so this just kind of goes along with everything that we’ve been learning. A lot of it really aligns together. Social studies covers a lot of world issues and so continuing that path of world issues really just kind of aligns, especially a complex text like The Hope Chest. It’s not an easy book for a lot of them to read, and they’re picking up a lot of new vocabulary in there.

Student: I would still say it shows a little bit of inequality and injustice in when she turns to go to the dining room and like…

Ms. Irvin: And so it’s a fantastic book of a fourth grader that’s taking part in this, so that they have a connection to the main character in the book, instead of a lot of the books have older people that they don’t have a connection with.

Student 2: Violet had stayed in hotels twice before and she’d gone to Scranton, and she’d never been in a hotel room that has its own toilet…

I think back to Ms. Rolph and Mrs. Gabhart and all the work they do to build background knowledge, develop communication skills, and give younger students every tool in the toolbox to be able to read and comprehend. By fourth grade, you can see how that plays out. Ms. Irvin’s students are navigating challenging social issues with ease — and they’re doing it with kindness and empathy.

Student: “I’m sorry, miss,” he barred her way. “Evening wear is required in the dining room.” Because, like, that’s not fair. I shouldn’t have more rights than you, right? So you shouldn’t have to wear different clothes…

Ms. Irvin: They’ve been very successful in handling those conversations. And a lot of them experience that background in their own families. And so, they care about those family members that were a part of this, or a part of the other units that we covered and really get to connect to that background and learn from them.

Principal: The students have the ability to really dive deep within that text and reading the text multiple times really helps solidify that learning and that comprehension for students.

(Atmos: Classroom sounds. Students chatter.)

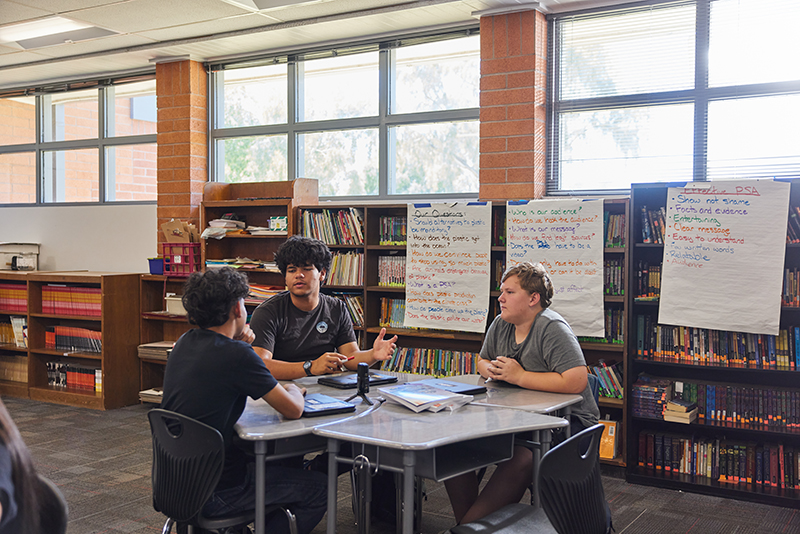

In Ms. Johnson’s seventh-grade class, everything comes together.

Ms. Johnson: I tell my kids I’m very strict. I’m a tough teacher, but I love them. I am very routine oriented. They know what to expect and they know that I’m fair. And so we have a relationship of, I love you, I will help you be successful, if you make a mistake, it’s okay, we will fix it — I will help you fix it, and we’ll move on. And the same goes with their learning. I will help you. I’m here for you. That’s why they pay me the big bucks, I always tell them.

Being able to collaborate, being able to think, being able to argue a point are all life skills.

If a student is not articulate enough to express their opinion and to explain why they feel a certain way, to be open to listening to other students’ opinions, to being able to work in a group, then they’re really missing a critical life skill.

I love the fact that students create — my students have created podcasts, they’ve created websites, they’ve created PSAs.

Ms. Johnson (to students): Okay, define the problem. Tell the people why it’s a problem, why they should get involved, and what you want them to do. Here’s the fun part. You may use pictures. You may use live action graphics, music. The sky’s the limit. You are the producer of this PSA. Okay, however you want to do it.

A group of seventh-grade students discuss ways to reduce plastic pollution in their community.

Student 1: So the target audience is towards people who want to help stop plastic pollution?

Ms. Johnson (to student): So do you guys have an idea of what you want, how you want to do it, what you want to…

Student 1: So we saw up there about like volunteers, so we’re thinking maybe about telling people how they can donate their time, they don’t have to donate the money.

Ms. Johnson (to student): Ooh, I like it, so doing your volunteer work and showing them how you volunteer, and that kind of ties into a plastic ocean … when they came up, they showed how people are volunteering? Yeah. That’s awesome. I love it.

Student 1: Like the beach cleanups.

Ms. Johnson (to student): All these plastic cleanups in the desert, except we don’t have a beach, unfortunately.

Student 2: If we focus around Avondale then we could use something that relates to people that live in Arizona or like around here and build up this and bring more awareness to it.

You can hear it too, right? The skills built in second grade, fourth grade, seventh grade — and every grade in between. You can hear students who speak with confidence, who really care for their community.

Ms. Johnson: Those are skills that they can take on in high school. They can take on for careers in the future.

Today, as I sit here reflecting on my time in Pendergast, what really stands out isn’t the high-quality instruction that I saw or the program that they’re using, it’s the commitment. The belief that students deserve better. Never is an instructional shift perfect or without challenge, but in Pendergast, they’ve chosen to see the bigger picture and are putting in the work. And really, that’s all we can do.

Next time, I’m going to share my experience with 600 educators at a training session in the School District of Philadelphia, a district also committed to improving reading scores.

Educator: I went back to my principal and I said, we need to make some major changes. We are doing a complete disservice to our school community.

That’s next time on Heart Work.

Want to put faces to the voices you heard today? Join me on YouTube at Imagine Learning to meet the educators featured in this podcast, and don’t forget to check out my reading list linked in the description.

This episode of Heart Work is produced by Justyna Welsh, Anise Lee, Danny McPadden — and me. Editing and mixing by Fraser Allan. Our recording engineer is Dan Victory. Artwork by Ellen Forsyth. Our executive producer is David McGinty. Music is from Universal Production Music. A big thank you to the Pendergast School District, Ramiro Alvarez, and Kelsie Pennington for welcoming us into their schools — and all the educators and students who opened their classrooms and shared their stories with us for this episode.

Heart Work is brought to you by Imagine Learning.

[00:00] The moment I realized I’d been teaching the wrong way

[01:20] Who is Lauren Keeling?

[01:52] A brief of reading instruction in the United States

[03:11] Arriving in Pendergast

[05:24] Reading as a passport to learning

[07:07] Inside Mrs. Gabhart’s first-grade class

[10:00] Building background knowledge with Ms. Rolph

[12:05] Relearning how to teach reading

[13:57] Challenging misconceptions

[16:10] Reading as a vessel for understanding and empathy

[22:22] Reflections

About the Host

Lauren Keeling is a seasoned education professional with a unique blend of experiences. A former broadcast journalist, elementary teacher, and principal, she now combines her passion for education with her love of storytelling at Imagine Learning. Above all, Lauren is a dedicated literacy advocate pursuing a doctorate in Leadership with a focus on Public and Non-Profit Organizations to further her impact on education nationwide.

Join the Club

Heart Work is our platform for telling educators’ stories. Sign up for the Heart Work Club to be among the first to share yours. You’ll also get the latest podcast episodes, articles, and exclusive content delivered straight to your inbox.