SCOTTSDALE, AZ – June 20, 2023 – Imagine Learning, the largest provider of digital curriculum solutions serving 15 million students in more than half the school districts in the U.S., today announced the results of a new study revealing statistically significant associations between math achievement and use of Imagine Math.

Imagine Math is a digital program that combines a rich curriculum with fun, adaptive experiences to engage students and help them become confident math learners. To understand the impact of Imagine Math on students’ achievements, the study analyzed more than 4,000 Idaho State Assessment Test (ISAT) math assessment scores from students in grades 4 through 8 in schools across four districts in Idaho during the 2021–22 school year.

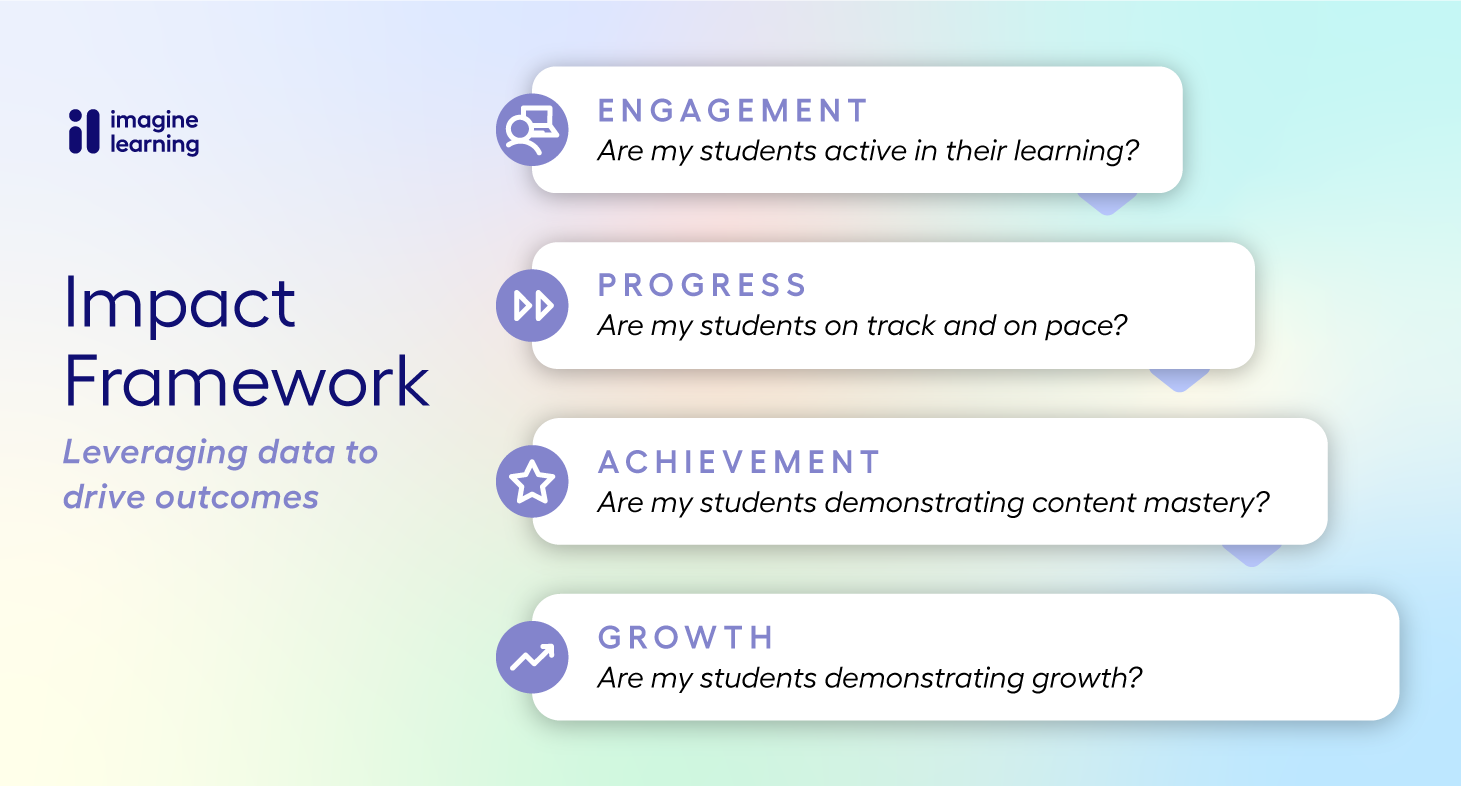

“For students to achieve success in any subject as measured across any number of metrics, they must be engaged and motivated,” said Sari Factor, Chief Strategy Officer at Imagine Learning. “Imagine Math’s personalized learning platform aligns with each individual student’s needs while providing the right amount of challenge to help the student achieve grade-level proficiency.”

Several school districts in Idaho use the program in a variety of different ways to supplement mathematics teaching for students with diverse academic abilities and standing. The study analyzed the relationship between software usage (active time, progress, and completion) and performance on the ISAT Math assessment, which was taken in Spring 2021 and Spring 2022. Additionally, it analyzed how the software affected student achievement based on other factors including grade level, English learner status, special education status, ethnicity, and/or free or reduced-price lunch status.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS

- The relationship between Imagine Math lessons passed and ISAT score growth is positive for all grades and statistically significant for grades 4 through 7. Students who passed more lessons in Imagine Math experienced significantly more growth on the ISAT math assessment than students who passed fewer lessons. Imagine Learning recommends students use the program until they pass at least 30 lessons over the course of the school year.

- The study also observed positive and significant relationships between Imagine Math lessons passed and ISAT math score growth for various student subgroups, including special education students, English learners, students who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, and Hispanic/Latino or American Indian/Alaskan Native students.

The rigorous, standards-rich content in Imagine Math adapts to the unique needs of each learner to develop essential foundations and conceptual understanding they need to be proficient at the appropriate grade level. Unique to Imagine Math, point-of-need access to live instruction by certified, bilingual math educators is available to make deep learning beyond the bell a reality.

Additional details on the analysis and a copy of the full report are available here.

About Imagine Learning

Imagine Learning provides digital-first PreK–12 solutions for core instruction, supplemental and intervention, online courses, and virtual instruction. Our mission is to ignite learning breakthroughs with forward-thinking solutions at the intersection of people, curricula, and technology. We serve over 15 million students — partnering with over half of districts nationwide. Imagine Edgenuity™ is our flagship courseware solution, complemented by Imagine Instructional Services’ virtual teachers. Our core portfolio includes Imagine Learning Twig Science®, Illustrative Mathematics®, and EL Education®. Additionally, a robust supplemental and intervention suite provides personalized instruction for ELA, SLA, math, coding, and more. Visit https://edu.imaginelearning.com/research-partner if you would like to become an Imagine Learning research partner.