Lauren Keeling (host): From Imagine Learning, this is Heart Work, an honest profile of America’s educators.

We are so fortunate today to be recording our very first-ever live Heart Work podcast episode, so feel free to cheer and clap and do all of the things that you want heard. Essentially, what we’re doing is elevating the voices of educators and administrators who are out there doing great work.

We have two of the most brilliant people in the room with us today telling the story of Marshfield Public Schools, which is a really interesting one.

We have Nicole Silva and Janna Murphy joining us, two instructional coaches who have been doing really hard work — not just selecting a new curriculum and moving into very different instructional practices, but also moving the needle in the direction that we want to go as districts and as teachers and leaders, to get to a space where we are inviting every child to the table and believing that every child is welcome to sit there and learn with us.

Can you take us back and give us some context for what it is we’re going to talk about today?

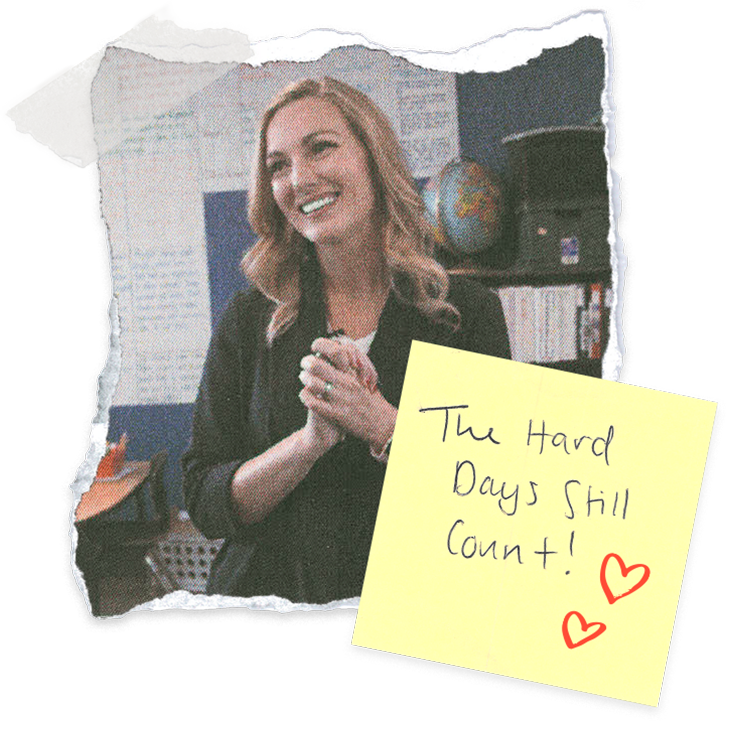

Lauren, Nicole, and Janna delivering their panel on making the shift to a science-of-reading-aligned curriculum.

Janna Murphy: We are, as Lauren mentioned, two instructional literacy coaches in the Marshfield Public Schools. We primarily work with teachers in kindergarten through fifth grade.

We were historically a balanced literacy district, and prior to that, all we had used was Journeys and some antiquated basal readers for quite some time. With our shift to the workshop model several years ago, we had a lot of growing pains that I don’t think were ever fully teased out once it came time for us to look into adopting high-quality instructional materials.

We found that we had a lot of work to do prior to adoption, and that spanned three to four years. It began with quite a bit of professional learning before we could actually begin looking at the selection process.

Nicole Silva: So we really tiered, or bucketed, our shift, starting with the pre-learning we needed to do with teachers and staff around what the science of reading is and how we start to make those shifts in our instructional practices.

We already had some really solid curriculum in place in Heggerty and Fundations, so we had our phonological awareness and phonics programs in place, but we really wanted to bring teachers along in this knowledge-building shift. We did some pre-work around learning about the science of reading through coursework and book studies around Shifting the Balance.

Then we moved on to how we are going to use this knowledge that we now have to look at new programs. We really adopted this notion of “go with your racehorses.” We looked at teachers who were interested in making the shift right alongside us, to join our team and start to look at curriculum and make decisions that way.

Now we’re in phase three, where we’re implementing and adopting and continuing the work that way.

Lauren: None of that is easy, and what I hear you saying, in a really big way, is you focus deeply on thinking about the human side of making a major shift like shifting to a curriculum that is aligned with science of reading best practice and research, and I am hearing you talk about some of the experiences that your teachers had prior, so using a basal, being a part of a workshop model — I was a workshop teacher, so as a kindergarten teacher, we were teaching in those workshops, and I loved it. It was a practice that was comfortable to me. So when it came time to shift, as your team is doing, into something else, it was hard, and I really had to think about what I was doing and why I was changing. I had good leaders like you who helped me learn about that, but we didn’t just jump into the curriculum. We took a step back. So I want to talk about that human lens and think through what you were saying in this very first phase, this very first step you took, which was professional learning, and getting people to see where you wanted to go.

Tell me about how that worked. What did you do? How did you structure it?

Janna: Yeah, so I think what worked in our favor in some ways is that we had — we’re coming back from a global pandemic, our teachers were brand new with a brand-new math curriculum, and so we kind of took the approach of, we went to our top-level leadership and said, from a literacy perspective, because we knew it was high time that we really start looking at what some of these shifts were that had been backed by science of reading research, and we kind of went to them and asked for permission to slow down in order to speed up.

So we said, can we actually build capacity with our teaching staff around why these shifts are important, what the research and evidence is telling us, so that they can make better-informed decisions when we actually start to look at curriculum.

So with their blessing, we were able to put our selection process on hold for a year and spend an entire year engaging in the Shifting the Balance coursework.

So in K through two, that book had already come out, and so we had all our K through two teaching staff participate in the actual course throughout that entire school year, and we paired that with what we call a GLC model, which is grade-level collaboration, but twice a month they met alongside literacy coaches and the reading specialists within their buildings to really unpack the work that we were doing.

So we all had this common experience and language with the course, but we also had this space for, OK, what does this actually look like in my classroom? And it allowed us to get into classrooms to really feel that with them. How could these shifts look? How do they match — or not match — what tools we have in front of us right now? And what would we need to bring in to actually support the remaining shifts?

In three through five, the book had not been released yet, and so we did a lot of professional learning with the three through five teachers, where we were pulling our own stuff and saying, “OK, this is what research is telling us. How do you see this fitting into your classroom?” And in the following year, as we were beginning to actually look at curriculum, the book had come out. So all of our three through five teachers were able to do their own book study simultaneously while we were beginning to look at curriculum.

Nicole: And I think the time that we spent with teachers in those grade-level collaboration meetings was such valuable time because we were able to hear their thoughts and perspectives and worries and concerns.

We did a lot with the Knowledge Matters campaign — pulling in blog posts and podcasts and then having time to come together as a team and really unpack what we have in our classrooms at this point that is lending itself to this type of work, and then, where are we really gonna need to target some of that deep dive of our curriculum adoption to make sure that if this is what the research is telling us, and this is what we believe as teams, what are we looking for in a curriculum as we start to move forward with adoption?

Lauren: And everybody magically got on board.

Nicole: (Laughs) Exactly.

Lauren: And believed it.

Nicole: Exactly.

Lauren: Right? Fingers crossed? So knowing that that’s simply not reality, how did you work with those who were not interested in making this shift? Those who maybe really loved the practices that they were holding dear.

Janna: I think what you said before, Lauren, about really feeling like you loved what you loved and that you felt passionately about the influence it had on students, we had to find a way to honor and embrace what was still working, while also taking that and pairing it with what the research was telling us.

I think that year of professional learning allowed us to see where there was still very valid space to keep some of that in play, while also exploring and maybe having to be a little bit vulnerable and notice that some of what we have been doing isn’t necessarily what’s best for kids anymore.

Nicole: Particularly in K–2, where we already had, you know, a sound foundation in a phonological awareness program, a phonics program, and we knew we were not going to throw the baby out with the bath water in that way.

We could, you know, remind the teachers it’s not all new. There are lots of things that are working well, and as we made our way through the process in general, we were pretty cognizant of reminding them in those spaces where there is a lot of new, but there you are still a teacher at heart and there is room for you to keep those practices that are near and dear to you that are supported by the research.

Lauren: I’m sure a lot of educators felt comforted in that and took comfort in not having to make a huge leap and change but easing into it.

Janna: I think so, and because we both come from the classroom and we both consider ourselves teachers at heart, we were able to take that year to build relationships and the trust that this is uncomfortable for us too. We have not taught this way either, and so it really allowed us to kind of team up and lean on each other while everyone was experiencing the different levels of discomfort.

Nicole: And I would say too, one of the ways, as we went through the book study, Shifting the Balance, one of our options for teachers was to opt into those a little bit early if they were interested in coming on board and being part of the vetting and adoption process. We called those our lab teachers, and one of the ways we really brought some more resistant or hesitant teachers along was by elevating their peers and putting people in place in buildings that would be able to take in the new learning, and also sort of influence and bring their counterparts along.

Lauren: I do wonder, you certainly had a gift in having a full year to be able to lean into professional development and work with your teams and your teachers. Not many districts have that opportunity. So if there’s one, while we’re in this phase, in this moment, what’s one thing that a district that has to, kind of, build the plane while it’s in the air, what’s something they could do to take from this process that you have done, if they don’t have that year lead-up?

Janna: If you don’t have that kind of time, which is something none of us have in education, really, I think it would be just making that a grade-level collaboration time or a professional learning community space that’s sacred, untouchable, for when those teams need to get together, whether they’re sharing the same podcast or an article or going on a site visit somewhere. I think the shared experience is what allowed us to have the conversations, that we weren’t trying to sell it because we had all participated in it together.

Nicole: Absolutely. Completely agree with that.

Lauren: That’s a great way to put it — shared experience. You can lean back on that, which you’re going to tell us about, I think, as we move into this next phase, which was you’ve done the learning, you’ve had the conversations, people are beginning to understand knowledge building or shifting to these different practices. Now it’s time to get into that space where you’re looking at actual materials and curricula and tools and gathering your people around to make that big, tremendous decision. So talk us through that part of your process.

Janna: Yeah, I think in every district, you have your go-getters, the people who really want to jump in immediately because they’re most comfortable when they’re staying a little bit ahead. We certainly had those teachers and tapped into them right away, but we also had some of our most resistant to change also wanting to be a part of the process because they wanted to make sure that their voice was heard.

And that actually really, really worked because it gave the selection committee, which ended up being teachers representative of each of our five buildings, an administrator from each building, a reading specialist, and coaches.

So there were about 30 of us on the selection committee at that point, and it did allow for some very colorful conversations around the myriad of feelings. But it was also really interesting because I think, so often, the people who rise to the top for those things are the ones who are always on the committees and always wanting to do that. So it was really helpful for us to go behind the scenes and tap into someone who maybe doesn’t and isn’t wild about this change, but has a lot of influence in their building or has the trust of their colleagues, and to kind of be able to bring them into the mix was really helpful.

Nicole: And it was also so helpful that we had had that shared experience, so that we could then calibrate what we were looking for when we went forward with looking at curriculum, because there were publishers that would come in and were very shiny and beautiful, but very reminiscent of the program we were coming off of, or something that maybe felt a little more comfortable, but if we brought it back to, is this actually what we’re looking for in a program, even though it looks beautiful?

That was really helpful for us to have that shared understanding to be able to come back to each time.

Lauren: So tell us a little bit more about how that shared understanding played into your selection process. What were your must-haves or your could-haves or your should-never-ever-haves?

You know, how did you work together to develop that process?

Janna: We were part of a two-year process with DESE HQIM adoption process, and so we participated with other districts in the state to look at high-quality instructional materials, and through that work, we were able to create a rubric for our district of what was really an absolute must-have, and we created the rubric based on the most recent evidence and the professional learning we had done. So you might really want this program to have leveled readers, but if that’s not necessarily what’s evidence-based, then that’s not going to make the cut for the rubric, kind of thing.

Yeah. And so when we came up with the pillars of what we really wanted to guide our work with, we then brought in the larger selection process team, and then they were able to tease them out a little bit further, specific to their work.

So, OK, we really want to make sure this is a knowledge-building program and that it includes authentic literature. Then, the classroom teachers and that committee tease that out further and say, yes, and the authentic literature must include X, Y, and Z. And so continuing to bring it back to that anchor of the rubric was what guided most of those conversations during the selection process.

Nicole: And we actually learned as we were developing the rubric that, if any of you have used the Shifting the Balance, the K–2 book is really a foundational skills focus with some of that language comprehension, but it doesn’t really go into the knowledge-building component.

So as we were, you know, creating our rubric and finding our look-fors, we were realizing that we did miss the boat a little bit with K–2, and we had to back up with them and really go into the knowledge-building and vocabulary piece that wasn’t so heavily emphasized. I think, when a lot of people think of the science of reading, they think of phonics, foundational skills, fluency, and decoding, but what we were really trying to highlight for teachers is that there’s much more than just those things, and we need to make sure that we’re finding a good mix.

Lauren: I think that’s an easy slip for teachers, districts, and administrators, that we know so much about foundational skills because that’s where we saw the greatest gap. And where we knew we needed to respond to our students and teach them those foundational skills so that they could read, but then we sort of forgot about the other part of the rope: comprehension, and actually, reading to learn. So being functional readers who are reading to learn things, that’s really important knowledge. So magically, everybody selected the same curriculum. Violins played, right?

So what we know is that that’s never true when you’ve got 30 people in the room, and they are smart and knowledgeable and they love their kids and they love doing what they do.

They find the curriculum and provider that came in and impressed them, and they hold on tight and they advocate for and they rally and they fight for that curriculum and they’re going to get everybody to vote for it because it’s the best one.

So with 30 people, I imagine you had a couple of really strong advocates in a couple of different directions. How did you manage those conversations?

Janna: Under the supervision of our assistant superintendent, who is really — she’s the director of curriculum — we had several meetings throughout that year where, once the publisher presentations were done, we had to look back at the rubric and really ensure that everything we had cited as being a priority was actually identifiable within these different curricula, and in some places, it wasn’t.

And then we had to be really strategic about the conversations because you’re absolutely right. People have really strong feelings, and if something felt either safe or like it was a good match for their teaching style, they felt strongly about it and were more than happy to share those feelings with their colleagues. And we had to be really careful about how we shared how we felt about the curriculum because, regardless of where we ended up, we wanted teachers to know that they had our full support as instructional coaches.

And so we were trying to remain very neutral so as not to rock the boat and say, well, we’re gonna end up with this one because this is the one that they want, and we really kind of just played this idea of like, bring it back to the rubric. What are we looking for? Is it meeting these needs? And if they are meeting the needs, let’s dig in a little bit further and find out which one matches your belief system or your philosophy better.

And it still was — it was still almost a dead tie with, we started with four, and we got it down to two.

Nicole: Yeah. And I think just like Janna was alluding to with us trying to stay neutral — being instructional coaches, our whole job is based on relationship building. And what we really, I think, recognized within this process was really about making sure everybody felt safe and heard and validated in moving forward.

So that even if the program they really wanted was not the one that was selected, they felt like we heard what they felt like was valuable within that program, and we were able to sort of highlight for them in the other program some similarities or some differences in why other people were feeling strongly about, for example, authentic literature was a huge — maybe it wasn’t, was it on a rubric?

Janna: Yes, it was on a rubric.

Nicole: It was on a rubric, and one of the programs that teachers really liked did not have enough authentic literature. So that was sort of a rub that we were balancing with teachers and just bringing them back to that being a priority for us as a district.

Lauren: You really had to trust phase one in this phase. You had to trust the process of the work that you did. Were there ever moments when you had to go relearn or reteach?

Janna: Definitely. I think we’re still bringing it back to that when things come up. I think also, any curriculum, it’s only as good as the person teaching it.

Lauren: Say that one more time, because it’s so true.

Janna: Any curriculum is only as good as the person who’s delivering it or teaching it, and so the idea behind the professional learning was that because no curriculum is ever going to be perfect, they were gonna be equipped with the tools to make decisions within their own classroom that were not going to compromise the learning goals of the program, but we’re also going to meet the needs of the kids sitting in front of them, because that’s what was at the heart of the work.

Lauren: So let’s go ahead and jump into, we have selected a curriculum. You are going to implement this thing. You are rolling it out. You’re getting people ready. How do you do that? Some people are unhappy. Some people are thrilled. Everybody’s in a really uncomfortable learning space. What’s next?

Janna: We have two things that we always refer back to. We have worked with a consultant for many years, and she would always say to us, “When people are unhappy, or when they’re grumbling and complaining, it’s because they’re growing, because growth is not comfortable.” And so we always reminded ourselves of that.

Nicole: And then the other thing she said was, “A plane has never crashed because of turbulence.” So we kind of keep bringing it — you know, in those moments when everybody is sort of like, you can feel the discomfort, it’s like, it’s OK, we’re learning and changing and growing.

Janna: We tapped into some fantastic teachers in the district and created a lab teacher model. So we support K through five buildings, and at every grade level, there are two representatives who work as the lab teachers for that grade level. And so within every school building, there are at least two, in some cases three lab teachers within the building that span the grades.

And those teachers worked alongside us the summer before we implemented to really just stay ahead and to really familiarize themselves with the materials, the instructional practices, and the philosophy behind the curriculum. So that was more of the, OK, how are we gonna be here to support them?

And then there was also the logistical pieces. Like with anything new, there’s just so much stuff, and we find more than anything else, it’s the stuff that bogs teachers down, and they don’t have time to sift through all the stuff. So we went through and actually created one-stop-shop documents, if you will, where everything you could possibly need to get you started for this first module is right here, embedded in here for you.

And that was between the lab teachers and that kind of logistical work behind the scenes. I wouldn’t say it was without its bumps, but it was a fairly smooth start. We did also, to back up for a second, we had some feedback from our teachers because they were, they were fresh off of a math curriculum adoption a couple of years prior to this, and they hadn’t had any professional learning around their new program for math until they came back in September.

And so there was a lot of feedback around the kind of angst that gave them over the summer, and so we did partner with the professional learning company that worked alongside our curriculum, and everyone received their first training in June before they went home for the summer, so that there was some groundwork laid that kind of allowed us to do some of the behind-the-scenes stuff over the summer.

Nicole: Listen, it was bumpy. It’s always going to be bumpy, but we felt like we had systems in place for the stuff, you know, the documents and where to go. But more than anything else, we really wanted to have the human piece, the human side of it in place in those lab teachers ready to go, in ourselves, ready to go, and just really reminding everyone, getting ourselves all calibrated around like, we are humans, and we are going to be uncomfortable. There’s going to be a lot of change happening, and there are people that you can go to to work through that, and that was our biggest, I think, accomplishment moving into it.

Lauren: I love the focus that you put on the human side of change in general, but especially instructional change. So let’s think about those two groups of educators that we always bump into when we’re in the middle of something that is change-related, right? We’ve got the early adopters who are all in, they are going to do this thing, it looks amazing, they love it, and they’re willing to do whatever you need them to do.

And then of course, we have our friends who grow roots and just want to do what they know, and sometimes, aggressively, but also sometimes, just want to — that’s what they’re comfortable doing. Talk a little bit about how we help those team members who just really like it the way they like it.

So you’re in the implementation, the curriculum has been adopted, you have support systems and they’re still standing still. How do you take baby steps with them?

Janna: We really kind of highlighted this idea of integrity over fidelity. Any curriculum is going to come with, do this and read this script and you can do this. And we said, in order to honor what these teachers already know and how they feel they can actually make change in these children’s lives, they have to be able to take this curriculum and make decisions with integrity, versus having to read a script. We were able to partner with them in a way that’s like, we would never insult anyone by assuming that this script that was written knows the students in front of you better than you do, and we named what some of those integrity versus fidelity moves might be. So we were like, you might decide that if there’s a protocol for your first graders, that is going to be way too confusing at this stage of the game, but there’s another protocol that they’re perfectly comfortable with that serves the same purpose, make that adjustment, make that change. We’re like, but what isn’t Integrity is, like, scrapping the whole lesson and ordering a packet off of Teachers Pay Teachers. We were balancing, what can we do here that is not going to compromise the end goal — the learning targets?

Nicole: We really wanted to honor these teachers who have been teaching for so long, who have so many tools in their tool belt that they don’t need to throw out. So I think a lot of the work we did, too, with the grade-level collaboration, those every-other-week meetings were invaluable because we could sit down together, we could talk through all of those growing pains, and you know, recognize and validate the things that they were doing that were working well.

And then when they had questions about — a lot of the questions we got were like, why are they asking me to do it this way? And so then we were able to come back to either the learning we did, or we were able to pull in another piece of professional learning to try and help teachers understand all of the why in the curriculum design, and talk through what is necessary, and then what is that integrity piece.

Lauren: I really want to point to something that you both said, which was integrity over fidelity. So say it with me. Integrity over fidelity. Ready?

Lauren, Nicole, and Janna: Integrity over fidelity.

Lauren: Because teachers are exhausted by fidelity. It’s a great word, but we’re exhausted by it. Integrity speaks to us in a different way, as you just evidenced by how you used that with your team. We talk a lot about our teachers who just need that extra help moving forward, but sometimes we forget to talk about our early adopters, those ones who jump in with both feet and love it, whatever we ask them to do. So as a district, as a team, how did you celebrate the gift that is someone who wants to try that brand-new thing?

Janna: I think we highlight them every opportunity. We got where they were invaluable to us last year and still are, but they’re so generous with their time too. They would so freely open their doors and invite their peers in, and so we really use that energy to create a site visit model where we could, principals teamed up together with other building principals to create a time where they could free up their teachers to go see someone else in action.

And all of that might have seemed like more work for the poor host teacher. It was also a celebration of how much they had dug in and how willing they were to share their successes with their co-teachers, which was so helpful to us.

And it was also — some of those early adopters got really into some of the community piece of the curriculum. And so a lot of their celebrations that we highlighted were the ways that they got the rest of the community involved in their work and people that they brought into the classroom. In a time where we have a lot less time to do that kind of work, they found the ways to combine the two, the new curriculum with opportunities that they used to have that they feel like they maybe don’t have anymore, and marry the two together, which was really nice.

Nicole: We also tried to highlight them as leaders within their buildings and within the district as much as possible, giving them opportunities to run sessions with teachers, either to preview upcoming materials or to open a Zoom room and let teachers at their own grade level pop in and ask them questions.

We also tried to rally everyone together in just saying like, change is hard, and we want you to find your marigold. So I don’t know if you guys have ever heard of the idea of the marigolds being the companion plant, and so, you know, we gave little flower pens to everyone and at each session we ask them to either write a thank you note to their marigold or make sure that they leave a little treat for their marigold or something to just remind everyone that, you know, find your person that’s going to lift you up and keep you going through this whole thing.

Lauren: That’s really lovely. And what a great way to example gratitude through hardship and really remember that we’re all in this together, and it’s best to be side by side.

So you are now in your second year of this implementation, and one of the things that I love when you talk about is that you really held onto that go slow to go fast. So you stepped into a major curriculum change in small chunks. Tell us a little bit about that.

Janna: When we mapped it out, we worked with one of our consultants to say, OK, in year one, these are going to be the things that we all do, and the curriculum we use is built on four modules. We said everyone’s going to, you know, attempt to get through these, and we paced them out, and then we realized as things were going that we were definitely not going to get very far through that last module.

And so then we paired back, and we recalibrated and decided what was possible in year one so that it could be done well instead of just hurling information at kids and moving on to the next lesson. So that was really helpful, I think, to shift our expectations once we were actually living it.

The other thing I think of in K through two — it was beyond knowledge-building curriculum, being a really significant way, a shift for the way we taught reading and did small group instruction. It was also a really significant shift for how teachers teach writing, and so that felt like a really big thing on top of the reading piece last year. We are really digging more into writing this year. We started with some professional development last spring to set the stage, and that’s really where a lot of our work is taking us right now, digging more into the writing piece in K through two.

Nicole: We did set up an instructional priority for us last year that was shared widely with teachers, and what we would come back to is this idea of really focusing on language comprehension through read-aloud and access to complex texts.

We wanted teachers to really get comfortable with that piece of the shift, and as all the questions about writing were coming out, we were taking it all in and setting ourselves up for this next phase, which is now like, OK, how does writing look? But reminding them we’re not going to be good at everything all at once, so just focus on this idea of language comprehension through rich experience with complex texts, and now we’re really getting into why writing is designed this way, how is writing in service of reading comprehension, and trying to phase it in so that teachers are getting good at one thing before we’re moving into something totally new.

Lauren: Very smart. So as we start to wrap up and think about what our takeaways are, if you could leave this group of brilliant people with one high-leverage practice, one thing that you did that you felt has carried through and made a difference from start to finish — well, not finish, you’re never finished, but from start to now. What’s one thing that you would recommend?

Janna: I think that having the luxury of that year we did for professional learning is probably very unrealistic in most cases, especially with some of the state’s requirements around HQIM adoption. But I would say having that really dedicated untouchable time for partnership cross district that has, I don’t think we’ve ever seen teachers lean on each other as much as they have throughout this, and it’s — our five buildings almost operated in like their independent silos.

And this has very much been like, because there’s district positions involved, has brought everyone together, and it’s allowed for that in-building collaboration and that very protected time. But the district has ensured that happens monthly across the schools as well as during our professional development hours on Wednesday afternoons.

So I think that suffering in silence in those silos would not have ensured a smooth rollout for this.

Nicole: The professional learning was what grounded us, and the relationship-building has been what’s sustained us, I think, just having that time and people feeling safe to ask questions or air grievances that we can follow up on because they trust us when they’re not understanding or trust us when they don’t agree with something. Having built that, just like Janna said, across the district now, like we have teachers saying, oh yeah, the teacher from this school just text me and asked me how I did that and they really didn’t know each other before, and now they’re in partnership with each other.

Lauren: It’s really remarkable what relationship-building can do.

Janna: One more thing I would add on, just as a quick plug. Our leadership — principals and assistant principals — engage with most of the professional learning alongside their teachers, and I think that went a long way because our principals and assistant principals have not taught knowledge-building curriculum before, and as the evaluators in the building, I think they were then able to understand the massive shifts that their teachers were making, but also have like a better understanding of what they were looking for in classrooms.

But why is that happening that way? And that was really important to our teachers, because they were accustomed to someone coming in and knowing that they were delivering small-group instruction using a leveled reader or conferring with a student, and so they felt uncomfortable perhaps with some of the new practices that they were using, and wanted to know that their building leaders understood why.

Nicole: And to add to that, they also really included themselves, and still do, in that grade-level collaboration time. So they were part of the conversations we were having about the why or the how, and the “I don’t understand.” They were part of that group mentality that we were all learning together. So that was really helpful.

Lauren: I appreciate you sharing that thought. It is so critical that everyone — everyone — is working to learn together. So as we start to think about what Janna and Nicole have shared with us today, we certainly know without anybody having said it out loud, that change is never simple. It’s never easy, and they have given us a lot of great thoughts and strategies around the steps that they took.

They would also tell you, I think, freely, and have already, that it’s been bumpy and there have been moments where they’ve had to reroute and think again. But we’ve sort of worked through a couple of things that we like to share that wrap up what Marshfield has done that they found successful. And one of the very first practices that I think we can all agree on is that you agreed to learn together. And that made a huge difference moving forward. You agreed to be partners in learning, so teachers, administrators, superintendents, coaches, all sat at the table together and learned side by side, shoulder to shoulder, reducing what sometimes feels like a hierarchy.

My favorite thing that you did is, you pointed to each other and those who were doing great things — you pointed out problems that other team members were having, and you pointed to solutions together. So you were constantly trying to shed bright light on good things that were happening and on collective struggles.

So I think that’s a really impressive element of what you’ve been able to scale. And finally, you gave permission to your teachers and your team to fail forward, which is kind of an overused term nowadays, but to just let people into the room and see how they do what they do, permission to ask hard questions, permission to push back, and want something different or want something more.

So we’re just so grateful that you’re willing to come and share that information with us. I have one final question that goes to both of you that you have to answer out loud. We want to know what keeps your heart in this work, because we know it’s hard. We know there’s not a lot that’s easy about what you do when you walk in the door every day.

So take a moment for us and jot down on that Post-it note what keeps your heart in this work, and I will gladly answer that question while you write. What keeps my heart in this work are the very human beings sitting in this room — listening to your stories, hearing how you’re solving really hard problems, how you’re solutioning and strategizing, and you’re making sure everybody has a voice and opportunity to spend time together. It’s inspiring.

Janna and Nicole, why don’t you tell us what keeps your hearts in this work?

Janna: I think what keeps my heart in this work is the people, the teachers, the students, and the community. And I think back to my first teaching days, I was in Washington Heights, in New York City, in a very underfunded school community.

And when I think back to that now, there is no reason why those children were not deserving of the same access to complex text, and that we expect all children to have access to these materials, and I think that that is, if I can really drill it down, that’s where my heart is, that this is in service of all students everywhere.

Nicole: For me, the relationships, the joy I get from seeing children and teachers learn together, alongside each other, and just the work of the heart.

Lauren: It is heart work, isn’t it? Yes. Appropriately titled, thank you so much for joining us on this panel. It’s been so fun. We appreciate y’all. Thank you.

This episode of Heart Work is produced by Justyna Welsh, Anise Lee, Danny McPadden, and me. Editing and mixing by Fraser Allen. Artwork by Ellen Forsyth. Our executive producer is David McGinty. Music is from Universal Production Music. A big thank you to all the educators and students who opened up their classrooms and shared their stories with us for this episode. Heart Work is brought to you by Imagine Learning.