October 20, 2023 9:14 am

Inquiry-Based Learning: What I’ve Learned

Imagine Learning implementation specialist and former social studies teacher Timothy Lent discusses the value of inquiry-based learning for students, strategies teachers can use to create successful inquiry projects, and why Traverse’s huge library saves teachers “a ton of time.”

Engaging Students with Real-World Contexts

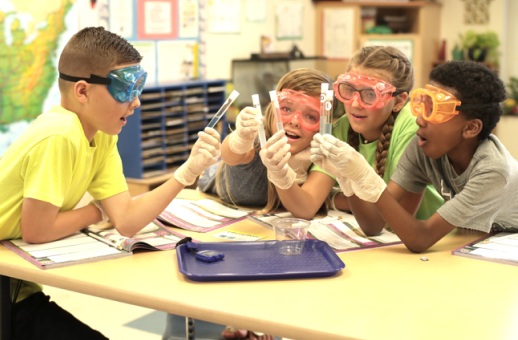

Inquiry-based learning involves getting students to actively apply their skills to real-world contexts through problem-solving activities. I use inquiry in my social studies classes because it gets students engaged and topics appear more relevant to them. By exploring problems, ideas, or questions through a range of different media sources and activities, students can draw their own conclusions, and the lesson is brought to life.

For the first three years of my teaching career, I used a more traditional style of teaching. Often, it very much felt like we were just going lockstep through history: this happened, then this, then this, then this. Every once in a while, we would stop to look at a source here or there.

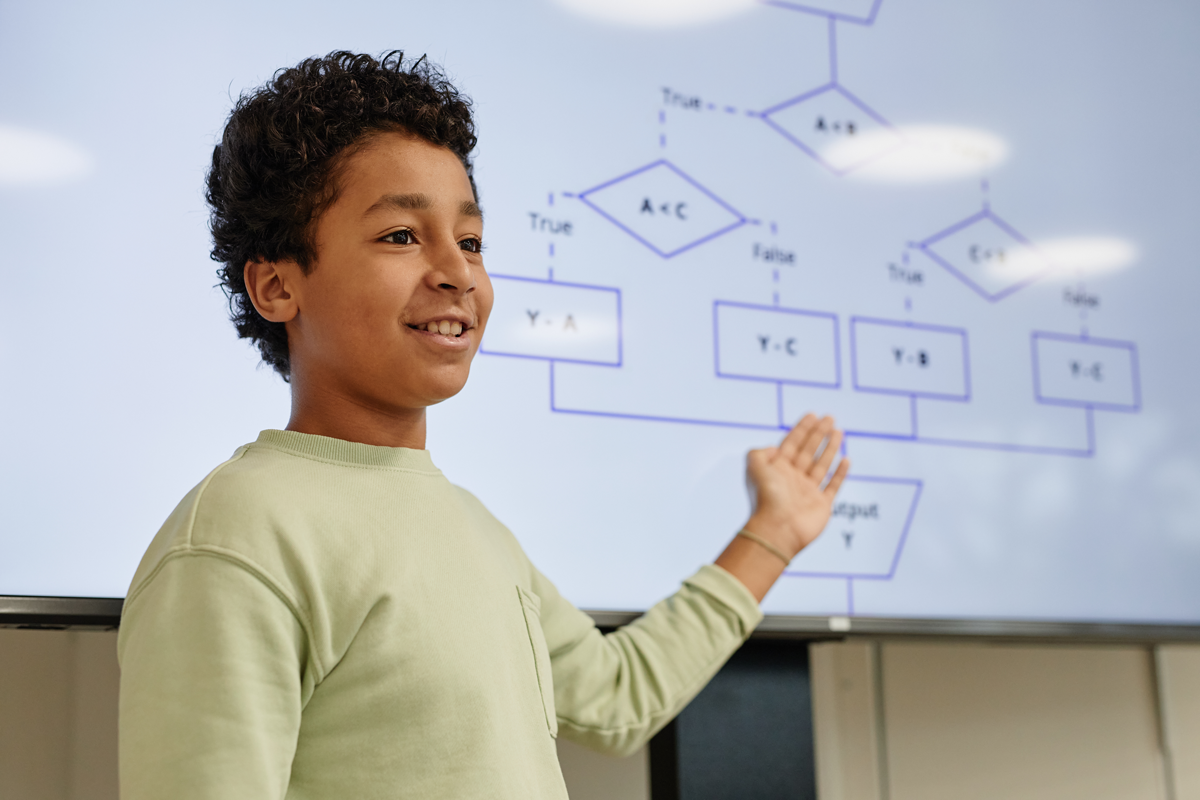

I was lucky enough to attend some workshops and be involved with some training that introduced me to the inquiry design model that Kathy Swan helped to create. When I started to introduce this method into my own classroom, I saw straight away that students became much more connected to what they were learning. We were still moving along chronologically—because that’s usually how you teach social studies—but instead of taking a day to look at a source, you’re really taking maybe three or four classes to breathe a little bit within a time period. Instead of telling kids what happened, you’re providing students with just enough context to get to the inquiry question so they understand what led up to it, and they can grapple with the question.

Inquiry in Action

At the beginning of an inquiry, you present students with the scenario: here’s the big question you’re trying to answer, and here are four or five sources that you’re gonna try to figure out the answer to that question with. And instead of students searching for the right answer to get the points, they now have the opportunity to come up with their own answer. Not only is this more interesting and more engaging, it’s also more challenging and rewarding to have to support a claim with evidence and then try to explain how that evidence supports the claim.

My first inquiry was on the Industrial Revolution, and by at the end of this inquiry, students were involved in a debate where they had roles—so you had students who took on the role of being child workers in factories, there were factory owners, there were labor leaders, and some of the kids dressed up for the roles. They prepared for it for a week and a half, gathering their evidence, from the point of view of their roles: “That testimonial is gonna be perfect for us” or “This piece from Adam Smith is perfect for me as a factory owner to prove that it’s just more efficient.” The students were the ones providing the momentum in the instruction because they really got into the debate and thought it was fun. It was very fulfilling to see as a teacher.

One of the biggest challenges of inquiry is finding the right question or right topic—if the inquiry is flat or the students aren’t so interested in the subject, you can look to implement a range of different sources so the students can draw connections to the subject, whether that be thematic or direct connections. Sources don’t necessarily need to be historical or traditional formats. In an inquiry about Black Lives Matter protests in July 2020, I brought in some tweets from a local reporter, Instagram posts from a student group, and a local news report, and the students had to figure out why the protests took place. They loved it because they could draw connections from people they were familiar with and work with media that resonated with them.

Finding High-Quality Sources

One of the reasons why Traverse is so valuable is because of the sources that have been selected. Most of them are really great quality and they’ve already been pared down. I think that’s incredibly important, not just for engaging students but also saving teachers time. It takes a ton of time for teachers to find sources.

Let’s say I’m teaching about the Whiskey Rebellion and I want to have five sources. I’ll probably pull a little excerpt from the textbook. I’ll look online, type in “Whiskey Rebellion, primary sources,” and then I have to read through all of them, and excerpt them, and they’re probably in PDF format so I need to find a way to copy and paste that. When I’m done with that, I have to actually create questions for the kids. And a lot of what you can find online is public domain, from 1916 or something like that, and written in a style that you need to translate for your students.

With Traverse you’ve got, for each chapter, a source set, a question already developed, activities for each source, additional source information in the Teacher Edition that you wouldn’t know about unless you did some next-level investigation on your own. And it’s so easily customizable, so let’s say there are six sources in the Traverse source set and I know we only have time to look at three or four, I just have to click a button and then those aren’t assigned to the kids. It just saves people a ton of time.

Strategies

Here are some tips and strategies that I’ve found helpful to create successful inquiry projects:

Using these approaches, I have witnessed the transformative power of inquiry-based learning in my classroom. I’d recommend it to any teacher who wants to not only enhance students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills but also help inspire a genuine passion for learning and a deeper understanding of their subject.

About the Author Timothy Lent

Timothy Lent is a social studies educator from New York State. He taught middle school and high school social studies in Brooklyn and Syracuse, NY and has years of experience in curriculum development and professional learning in schools, non-profits, and for-profit companies. He is now a Professional Learning Specialist at Imagine Learning, training educators who use IL’s innovative social studies program, Traverse, to develop the next generation of informed and active citizens.